my brief feud with chantal akerman

I take the Paris tram to work every day and yet I did not notice until recently that one of the stops along the T3b is called ‘Delphine Seyrig,’ presumably after the actress-cum-filmmaker best known for being Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles or as the unnamed woman in Resnais’s Last Year at Marienbad—the latter of which I have not and am in no hurry to watch because I am quite decidedly not a fan of either the former or Resnais’s other oft-considered masterpiece Hiroshima Mon Amour. I have been, to some extent, scrutinized for disliking Jeanne Dielman. The film most recently topped the new Sight & Sound poll in 2022 and has thus scored an ‘official’ point towards the designation of the greatest of all time: a statement I purport to be both ridiculous and self-defeating as well as a legitimate example of true intellectual snobbery (some amount of cultural tastemaking and gatekeeping is good for the form, but this particular phenomenon really borders on parodic). So this article is an attempt to put this misconception to rest once and for all: neither do I think that Chantal Akerman is a bad filmmaker (in fact I think she is really very talented and intelligent) nor do I think Jeanne Dielman is a bad work of art. But there are things I have to say about this film and its position in the canon regardless, and several of these things are quite negative and not very nice to hear—they play strongly at what my own personal notion of the ‘cinematic form’ is and are derogatory towards people who perceive cinema as something starkly different from what I purport to understand it as. Yet I will say them, and because they quite directly address certain talking points I find tiresome and generally prefer not to engage with I will not hold back but lay them to rest once and for all.

you’ll never walk alone

The complications that arrive while determining the position of Jeanne Dielman in the cinematic canon arise from what is essentially a mismatch between intended and actual viewership. Barely anyone who watches this film is actually attempting to engage with this in the level that Akerman intends, I believe, a fallacy which is best exhibited by the constant proclamations of this film as a feminist masterpiece. This is not technically wrong—the film is, by nature, a feminist film—but in function the way that this designation is used is really quite incorrect. Here is the gist of it: Jeanne Dielman cannot be a film about the extraordinarily demeaning and sexist nature of domestic work because the titular Jeanne is not an accurate representation of a housewife.

This doesn’t mean that the film doesn’t deal with sexism or the ways in which women are demeaned. It simply means that it cannot do so on a level that has to do with the performance of domestic labour. What I am also not trying to say is that individuals with Jeanne’s problems don’t exist in this world—they certainly do, and they are to be pitied and empathized with, and it is a grave mistake on part of society that we do not help them. But the lens through which Jeanne Dielman views domestic labor is completely at odds with how domestic labour actually manifests in this world.

What I talk about on this blog is often filtered through my perspective on societal functioning, which I suppose can be broadly cast as ‘communist’ but in a manner that is closely linked to yet different from what the symbolic definition of that word now is. It is easy to think of ‘socialism’ and ‘communism’ and imagine failed brutalist states, mass hunger and ever-rising taxes. But the words possess a literal meaning to them as well—they contain ‘social’ and ‘commune’ in them, and deal with the responsibility that society has to its individuals. It is easy to fall victim to the American ethos1 of ‘each man for themselves’ and forget that society functions in a way that often has nothing to do at all with nations or forms of governance. We have responsibilities to our children and our neighbors, and as much as you hate the homeless drug addict on the street you would try hard to love him and help him if he was your son. This is not because of moral principles, but because of the raw, biological urge to love your children. Of course you love him. And you want him to be happy, and so you do what you can.

Our principles only fail to synchronize when I try to claim that the government’s job is to ensure this responsibility, but it is not an unreasonable response to that question that the people who my taxes are going to help are not people who live in the same society I live in. In fact, that is a very good response—the technological and ecological complexity of the world is now so vast that ‘societies’ span far more people than you could ever consider being part of your tribe. But the underlying sense in which I use the word ‘communist’ has far more to do with this notion of community that I just prescribed. Human societies have a way of forming and genuinely working. Niches, like housewives, are not created in isolation. It is easy to think that the reason why the world sucks is because there are bad people who think the wrong way and cause problems. It is remarkably easy to watch Jeanne Dielman and say, hey: look at how sexist men are, millions of women suffer like this every day. But these generalizations completely ignore the fact that society does not exist in a vacuum, and that these trains of thought have often developed for very strong reasons. In the case of housewives, the fact of the matter is that housewives like Jeanne Dielman are far and few between. In reality, most housewives are extraordinarily social and constantly in conversation with other housewives: when they go on the street, when they go have tea with each other in the evening, when they cook together. Living a life like Jeanne does in the film is a recipe for breaking apart at the seams (which is, of course, exactly what happens to her). Such a society consisting of individuals largely like Jeanne could not effectively function, at least not in a world that allows a film like Jeanne Dielman to exist. Does this mean that housewives are happy, or that they are not exploited? Of course not. But the manner of their unhappiness and unfreedom is something not expressed in the film, because Jeanne is not a typical housewife. She is far less alive; she does not possess any of the natural defenses conventional housewives possess against malaise and eventual suicide.

Chantal Akerman is quite obviously a genius, and her own individual perspectives on the film are significantly more revealing.

Akerman called Jeanne Dielman a feminist film, but not a militant one: Jeanne is neither a role model nor an example of a victim2.

This movie represents a problem that could be lived by a man as by a woman.3

In truth, the ‘problem’ that Jeanne possesses is not inherent to being a housewife, but rather the far more insidious problem of profound depression due to modernity.

I like to compare Jeanne’s problem in this film to the problem of the protagonist of I Saw the TV Glow, which is quite possibly the worst film I’ve ever seen in my life. The underlying attitude of this film is that of being cruel to those who do not have the power to express themselves; it is a film that is so utterly steeped in this capitalist ethos of hyperindividual self-actualization that its prescription to those who fail to actualize is deserved unhappiness and eventual death. What a nasty, horrible way to think! This is how modern capitalist society conceptualizes therapy: as an individual problem, as if it is your own duty to keep yourself healthy. If a person kills themselves, it they themselves that have wrought such a fate. Both Jeanne and the protagonist of that film have the same problem: they have fallen prey to profound depression due to existing as individuals under capitalism, and they do not possess the strength nor the support around them to propel themselves towards being saved. We do not see Jeanne talk to other housewives or participate in any society-wide activities, despite living in a Belgium in 1975 that consists of far more than merely people self-isolating on their cell phones all day. In effect, she has been reduced to a ‘loser’—a person who basically does nothing, and consequently is a negative void of existence. Jeanne has a horrific life and does nothing at all to fix it; it is not her fault that she turned out this way, but the fact of the matter is true regardless.

The difference between Chantal Akerman and Jane Schoenbrun, of course, is that one of them is a great filmmaker while the other is a hack, and in this case Akerman has a full and complete understanding of what her film is about. Ultimately, Jeanne Dielman is an exercise in literalizing the passive weight of existence—a feminine counterpart to something like Radiohead’s OK Computer, where the motions reveal an existence haunted by the melancholy and the everyday in the absence of genuine connection, in the absence of the real, in the absence of life-and-death danger until the existence itself becomes so decadent and heavy that it begins undoing itself. It is about how modern society makes it possible to lead such an existence, and how even a slight deviation towards life is enough to break the fragile human brain.

Is Jeanne Dielman feminist, then? Unquestionably, because the decision to make the film in the manner of its current existence—that of being represented as the plight of a housewife—is inherently feminist, but it is a baser, more exhaustive form of feminism than a mere ‘display’ of perpetrated oppression. Akerman, again:

Akerman, again:

I understood the importance of the film many months after finishing it. In the beginning I thought I was just telling three days in the life of a woman, later I realized that it was a film about the occupation of time, about anguish: doing things in order not to think about the fundamental problem, that of being.

I do think it's a feminist film because I give space to things which were never, almost never, shown in that way, like the daily gestures of a woman. They are the lowest in the hierarchy of film images.

If I could paraphrase it better, I would try.

with great power comes great responsibility

Taken as a meditation on existence, Jeanne Dielman is obviously an exceptional piece of art—it is able to successfully evoke the feelings it attempts to evoke. Perhaps even too successfully; the film is rather uniquely affecting.

Where this becomes frustrating, however, in its evaluation as a piece of cinema, which is a lot murkier. There is more to cinema than pretty images, and I am not denying that Jeanne Dielman is good cinema, but it is quite concerning that the so-called #1 greatest film of all time possesses exceptionally few qualities that have become staple of the cinematic form. The fact of the matter is that beautiful characters, whip-pans and crash zooms are cinema—laugh at them all you like, but this is exactly the power that cinema provides, which is something that Jeanne Dielman simply does not fully leverage. Jeanne Dielman can function as an art installation consisting of a series of stills, but something like Breathless could never be anything but a film; it is so utterly entrenched in the form so as to be inseparable from it. Must it not be so that the greatest films be so cinematic that the nature of what they communicate be inherently meaningless in the absence of the form?

That the vast majority of critics watch Jeanne Dielman and immediately categorize it to be one of the greatest movies of all time is a strong indictment of film criticism as an institution; it is astonishing that a film that possesses so few of the qualities that make cinema great is lauded as a top 10 masterpiece by nearly all critics—the lack of institutional diversity which proves, yet again, that whatever ‘white male’ school of criticism used to exist has now been replaced by an equally performative group that still ascribes the highest grade to European bleakness. The playbooks are all the same: slow cinema, formal preciseness, an intensive obsession with pessimism and the negative. It is not that any of these things are inherently bad, but rather that they paint cinema as a dry, meditative enterprise, when it is the most dynamic art form to exist. Where do these qualities emerge? When were they elevated? Who knows? Who cares?

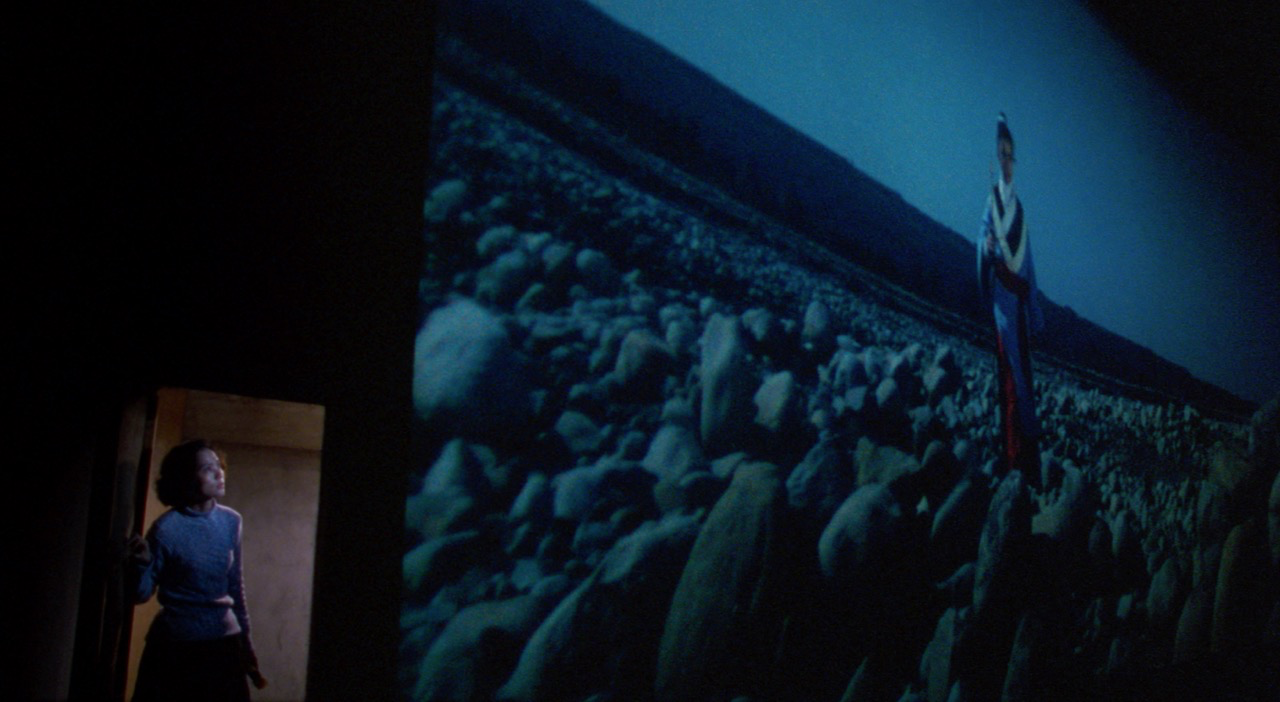

I am not the biggest fan of slow cinema, but there is several I like, regardless—Tsai Ming-liang and Hou Hsiao-hsien being the most straightforward examples, both of whose films often consist of nothing more than static images played after the other for a couple of hours. This is meditative thematic elevation not very different from something like Bresson or Tarr, but the purpose is not to depress— in fact, echoing the underlying buddhist principles of the societies from which these films emerge, the purpose is to create a meditative experience that brings you closer to the medium. The way this manifests is in terms of the actual films is the images that they choose to show. Why is it that the cinematic interiors of Ming-liang are less lauded than Akerman or Tarr? The answer is due to elevating bleakness to the peak of the form. I personally find this garish, really—think of our great auteur Paul Schrader, constantly wondering if anyone has made a better film than Pickpocket. Schrader himself has made at least five films better than Pickpocket, because he takes the Shakespearean stance of American cinema—that it is possible to express things through good stories and good narratives, and though there is significant artistic and experimental merit in the form of expression employed by directors like Akerman, it is not what cinema does best. There have been a gazillion movies made throughout history. The vast majority of them have been crappy pulp. Denying this fact is akin to denying cinema itself—it is not the masters that define the medium, but the medium that defines its masters. I will continue to laud À bout de souffle as the greatest; the film that contains in itself more than any other all the things that are good and lovely about cinema—a film as tragic as Jeanne Dielman in what its Marxist undertones set out to describe, and yet a film that also has two people making love and pointing guns act each other. It is a culmination of everything cinema has the power to do.

And, look: I love America. The fact that the greatest society the world has ever had4 followed from what is essentially the antithesis I of what purport to support has not gone unnoticed by me. Someday I will know the answer to how such a thing happened, but for now I’m going to assume that it has something to do with the protestant work ethic.

Janet Bergstrom, Sight and Sound, November 1999.

Marion Kalter, Interview with Chantal Akerman, 1977.

Well, second-greatest. Where were you when Rome fell?