that g.o.o.d kid is gone

Until recently I had never watched a Jonathan Demme movie. A sort of shocking confession on my part—I do know generally everything about The Silence of the Lambs, and I’m sure I caught it on HBO as a teenager, but that was so long ago that I might as well have not watched it. And though I’ve watched the clips and seen Tina Weymouth do that weird monkey shuffle thing on stage I’ve never watched Stop Making Sense, either.

and you may ask yourself: “how did i get here?”

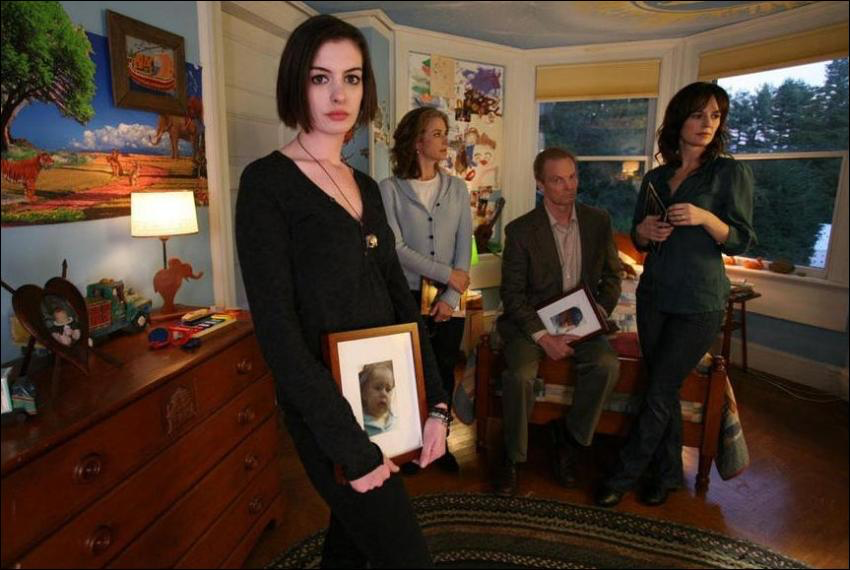

What I did watch that took away my Demme-unfamiliarity (and inspired me to write this blog post) was 2008’s Rachel Getting Married.

Over the years I have tried very hard to ascertain what particular manner of movies appeal to me. Finding the answer always seems to be a losing proposition. For a while there I thought that I generally disliked slow cinema, but Hou Hsiao-Hsien’s Millennium Mambo and Tsai Ming-liang’s Goodbye, Dragon Inn proved me wrong—the latter, in fact, is basically just a collection of near-still images set to music and the sound of King Hu’s Dragon Inn playing in the background. The difference between these and the more European style of slow cinema which I have a general distaste for is perhaps the actual images appearing on screen. It is not necessarily true that a slow pace is what puts of me off, but rather slow slogs through grimness à la Theo Angelopoulos, which is really what characterizes all the neorealisms that European cinema seems to have latched onto; Godard has his 8-minute tracking shot in Weekend, sure, but that fascinates me beginning to end.

But it is not true that simply images that I like comprise a good movie or else I would be a fanatic for Bertolucci’s The Dreamers, which I nevertheless find poor in both conception and execution. I guess what I’m really looking for is this manner of psychological complexity which can only really be expressed as strongly expressing the interiority of the characters through their actions—and in the case of cinema the scene (but I don’t mean the mise en scène—this always strikes me as kitschy). It is always important that the actions of characters not be explicable, but correct, even so.

What do I mean?

Perhaps it is easier to explain what I don’t mean. There is a sharp tendency in modern storytelling to think of characters as bundles of attributes—as if their personalities can be neatly sorted into likes/dislikes, experiences, pivotal moments, relationships… you get the gist. ‘Modern storytelling’ is probably an erroneous term, but there exist at least a vast amount of resources available on the internet geared towards this mechanization of writing which spends a lot of time on things like ‘consistency’ or ‘believability.’ It is kind of like applying the three-act structure to how characters progress in the narrative. There is already a fallacy here insofar as it already simplifies the conception of the character to something that can be managed through something resembling excel sheets, rendering them generally inhuman. The potent example here is anime, because it is quite explicit in terms of power scaling, but it is also more generally applicable to something like the film Anora, in which the titular character’s ‘arc’ is so explicable as to be rendered moot—I can pretty much describe the psychology of Anora’s ending in plain English. This is essentially the most damning criticism I can give of a film—that the film does not even use its visual language to construct an experience which is inseparable from the cinematic form, and is in fact replicable just by a verbal description.

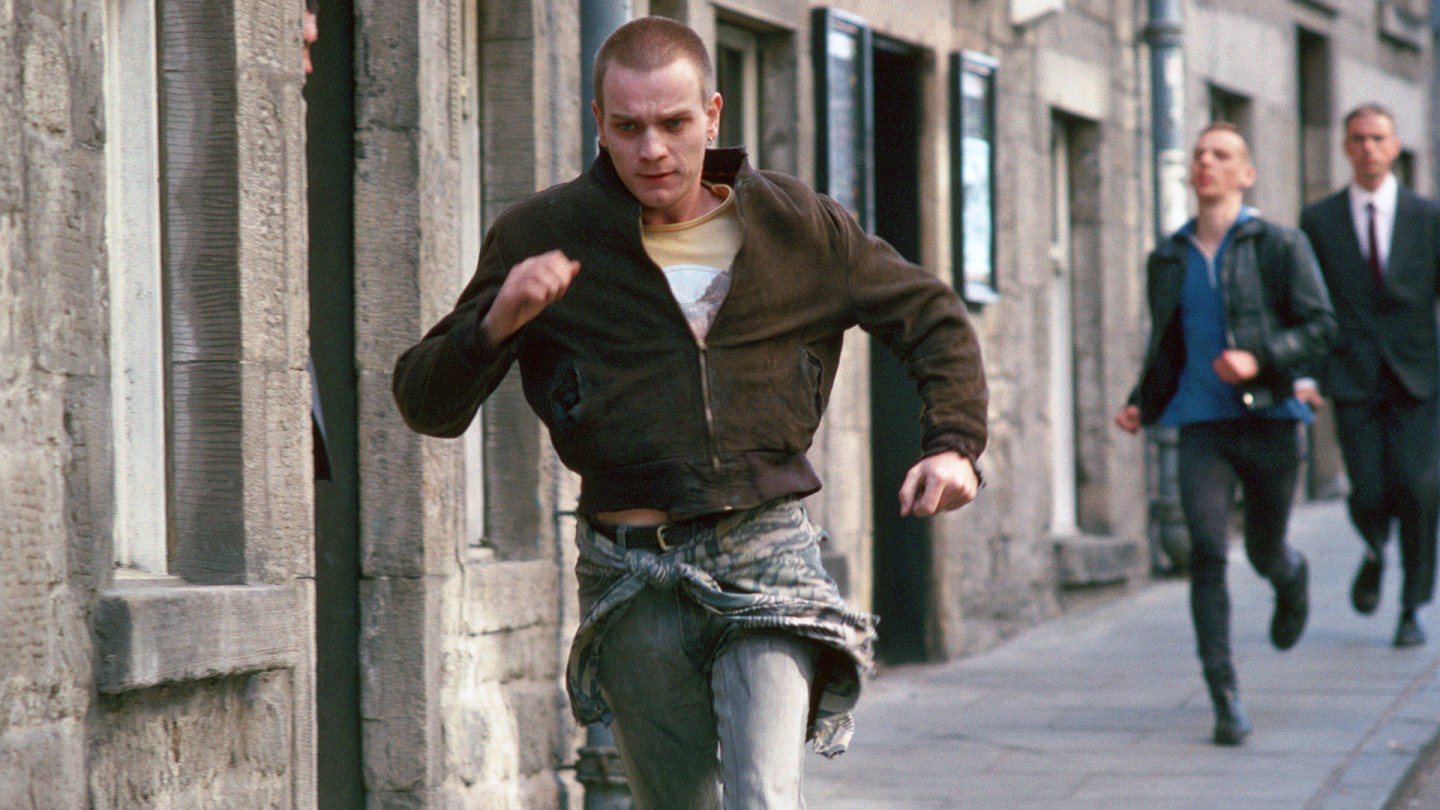

In terms of something like Anora, the usual argument goes that this psychology renders the character believable. And it is true that real people do sometimes follow the kind of arcs closely associated with movie characters—movies are quite good at portraying addicts, for instance, and though the films they star in have an unfortunate tendency to be banal and repetitive, I am not going to argue that they get the fundamental psychology wrong. Because the external psychology of a recovering addict sort of does loosely correspond to this three-act pattern of recognition → failure → recovery.

But I have to interject here with two observations:

- It is not the job of a movie to portray ‘believable’ characters, and there is no rule that states that characters have to be believable or accurate to be good or entertaining, or even that believable characters are any kind of component of a good film.

- While such structures may correspond to accurate external, observable psychologies, cinema as a medium has developed a vast amount of techniques to express the characters’ internal psychologies, which often (or even usually) do not correspond to any such easily definable or expressible patterns.

The kind of writing I describe above is something I don’t appreciate or enjoy, but it has its appeal. Where it falls completely flat for me, however, is when it is applied to characters dealing with or overcoming their ‘trauma’ (a loaded word, and not one I like to use—I am generally opposed to psychotherapy verbiage). It is really astonishing how poor films are at handling this particular aspect of humanity. The techniques seem to be quite stale: now I am by and large a big defender of Good Will Hunting, but the “It’s not your fault” sequence (although I love it in the context of that film) has caused irreparable damage to how movies approach cathartic moments of recognition, and the alternative just seems to be delving into Bergman’s worst proclivities and simply smearing walls with red or something as ‘symbolic’ representations of trauma (pretty much Ari Aster’s entire career). Neither of these are good. The latter looks flashy but has no substance. The former does not lend itself well to serious dramas.

The misconception here is that the language of cinema is not a language of metaphor. Cinema does not need to allude, because it can simply show—the need for allusion is caused by inherent limitations of the form. Then allusions through the mise en scène—which I described previously as kitschy—can be ‘symbolic,’ sure, but don’t really serve a purpose when you sacrifice actual psychological complexity in the characters in favor of the symbol. I’ve mentioned that this is a habit of Bergman’s, but it’s also an unfortunate one of Kieślowski’s in Blue which by using the color as a symbol of Julie’s grief outsources recovery away from the character and leaves her kind of flat. In Red, on the other hand, I don’t think the color really means anything, and therefore whatever is left is a complex interplay between the actors and the people they are portraying and the film becomes very compelling indeed.

Okay so then what is a film that actually does well with the psychologies of the people involved? My go-to answer is Guadignino, who has made a whole career out of this sort of stuff, but does it pretty entertainingly in this clip from Challengers.

I like Challengers because at no point during the runtime of the film is it clear what the priorities of each of the characters are or what they want from each other or really even what they want in general, but every decision the characters make, nevertheless, is perfectly in character—Guadignino manages to communicate the personalities of the characters without making them even the remotest bit explicable, and it is really quite unclear what they are going to do next or why they are going to do it. This is one way to make something psychologically rich. A method that is more naturally ingrained in the concept of a scene is this sequence from Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, in which Tom Cruise (wandering the streets of New York City lonely and disturbed after a heated discussion with his wife who recounts her adulterous thoughts) encounters a manifestation of his deepest desire at that moment: a woman willing the spend the night with him. The subtleties here are so rich that the last time I watched this film, my friend paused the DVD midway and exclaimed “this is completely insane!”—referring, of course, to the sheer ingenuity and the hundreds of thousands of moving parts here that comprise a really bizarre encounter that’s impossible to look away from.

and you may tell yourself: “this is not my beautiful house”

Out of all the 1500 or so movies that I have gone through in my lifetime, there is no film which achieves a blend of all these types of ways to maintain psychological richness while having the clear intent to explore a character that has suffered through grave amounts of trauma better than Rachel Getting Married. It may very well be one of the greatest movies I have ever seen in my life.

To briefly recapitulate, Kym Buchman is a recovering drug addict returning to her childhood home for a weekend in the hopes of celebrating her sister Rachel’s wedding. Rachel is much better off than Kym—she is finishing a doctorate—but the nature of their relationship is unclear; it seems as if they were very close in childhood, but Kym’s history of self-destructive behavior has caused a rift in their relationship. She is also dearly loved by her father, who is helping organize the wedding, but is mortified by how she is being patronized by him. It’s unclear how much Kym has ‘recovered’ or whether such a recovery is even possible and if so what it would entail. Over the course of the weekend, a variety of hard-to-watch events occur as Kym tries to reintegrate into a family that really does want her back.

There’s a lot happening here, which is a good thing. Kym’s struggles are complex and multifaceted, and a simple treatment would not suffice. I mentioned earlier that the history of cinema has developed a variety of methods to capture the internal psychology of characters; the one Demme employs here is his handheld digital, reminiscent of the claustrophobic cameras of something like The Office which also notoriously uses them to provide a POV of similarly ‘embarrassing’ moments—except in Rachel Getting Married the embarrassment is sincere and almost dreadfully unfunny.

What really gets me here is that it is so, so clear that Kym is trying. Before we get to know her we think she’s a bit of an entitled brat who doesn’t understand the consequences of being a narcotics addict and wants to leave rehab and shove it off as if it’s nothing. But even people who know and understand that they are addicts want to leave rehab. When we see her go to a narcotics anonymous meeting it seems as if she doesn’t really want to be there, and it’s true—she doesn’t want to be there, but she only doesn’t want to be there as in she wants to be the kind of person who doesn’t have to go to NA meetings to survive. Even before she goes to the NA meetings the scene is so palpable so as to be nauseous. It is so clear that her Dad loves her but worries for her and is trying to pretend as if he doesn’t, which is what Dads do. It is so clear that her sister loves her but can’t shake off the years and years of resentment she has gotten from being unable to deal with Kym’s nature. To someone like Kym this is the kind of dreadful atmosphere that exists in an exact opposition to the affirmation she needs to live. None of these people ‘make sense’—it is impossible to capture what is going on in their heads in a sequence of words because their feelings exist only as fleeting bundles drawing them to actions inside their mind. But the expressions of these feelings are genuine and tenuous.

I guess the reason why I am so concerned with the behavior of her family the sheer moment Kym arrives home from rehab is because there is this disjunction between what her family think is the correct thing to do and what is the thing that they have been told to do. Ideally they would tell Kym to put on something nice, or get a nice haircut, or something, if she wasn’t in the state that she was in. But because they don’t have any understanding of what she is ‘going through’ they also don’t understand that Kym’s problem isn’t that she wants to be allowed to do whatever she wants because any restrictions that would be placed on her would act as triggers, it’s the precise opposite—she wants to be treated as she usually would because the ‘trigger’ is the acknowledgment that something is off. In her case her reaction is annoyance, then guilt, but really something more than just that and more of a mix of both combined with heightened stress and a deep love for them for even trying. The actual state of her brain is one that appeals immediately to your heart; it is so easy to empathize with, but nearly impossible to capture verbally with any kind of accuracy. Like, it’s her sister’s wedding. She wants to be happy and enjoy it.

The aforementioned scene—the one in which Kym goes to NA—arrives sufficiently early on to ensure that we learn that the thing that is driving Kym insane—the thing that has caused her to recover to whatever extent that she has—is the fact that she was responsible for the death of her younger brother during a car accident in which she was driving under the influence.

And I struggle with God so much, because I can’t forgive myself. And I don’t really want to right now. I can live with it, but I can’t forgive myself. And sometimes I don’t want to believe in a God that could forgive me. But I do want to be sober. I’m alive and I’m present and there’s nothing controlling me. If I hurt someone, I hurt someone. I can apologize, and they can forgive me... or not. But I can change.

And this is Kym in 2008, ten years in and out of rehab, struggling, and it’s so hard to tell whether there is any understanding or recovery or what is even going on in that head of hers. But we know that she’s trying, that this is not a joke to her.

There’s a lot of other stuff that happens in this movie and there’s a lot of places where it hits, some even harder than this one. But the common thread as you go on is that despite the fact that she is trying it is still really hard to give Kym the kind of forgiveness that she wants or that she deserves. It is hard because it is true that she is not, like, a ‘normal person.’ She doesn’t behave the way that she should and it is understandable that she doesn’t behave the way that she should but it is also frustrating that she doesn’t behave the way that she should. She does awful things and can’t control her emotions and drives a car into a tree. What emotions are these? Unclear, but all we know is that they are overwhelming and negative.

Of all the scenes in this movie the one that I find perhaps the easiest to psychologically articulate is close to the end where she doesn't stick around for the rest of the party and leaves. Just walks away. The dismal sense of abandonment is so large that Kym is literally unable to even exist around happiness until it feeds on and drains her life force out of her. There is no faith, good or bad, in which she could participate in something like this. It’s not that she doesn’t have the inclination or that she believes that she doesn’t deserve it. It’s that she doesn’t have the capacity. That this is impossible for her is a fact as simple and true as the sun rising from the east. She was not designed to exist around such things. It is not possible to exist around your family when they are presenting to you an infinitude of love while you have been trying for so long to get them to hate you. And yet she wants to feel some semblance of affection because this lack of it is somehow even worse. So she lights a stupid lantern as if it has meaning when it doesn’t. When you are hurting so badly in every single atom of your body it is not possible to exist reasonably around your beautiful sister who you love and who is getting married as she decides not to seat you on the family table because she doesn’t want you to make a scene when you know you are not capable of that.

It is a fact of nature that people will be mean and that people will be cruel. But it is not easy to understand the kind of damage cruelty inflicts upon people. People are cruel to Kym. It is not easy for her and it is not easy for them. But it inflicts upon her an ardent desire to be home and to never be forgiven. To someone who already inflicts so much cruelty upon themselves it is even worse to find your loved ones agreeing with it, too.

But the wedding happens, and it goes well, and in the very end (because this is not a cruel movie, and it is a movie that carries with it empathy for all the people within it and for all the people in the audience watching it, too) the sisters embrace and Rachel shows genuine love and affection to Kym because she is, after all, her sister, and they were close and despite all that happened they are close. And that gesture is not enough to cure Kym because no gesture will ever be enough, but it is something. And they are happy, if only for a brief moment.

and you may say to yourself: “my god, what have i done?”

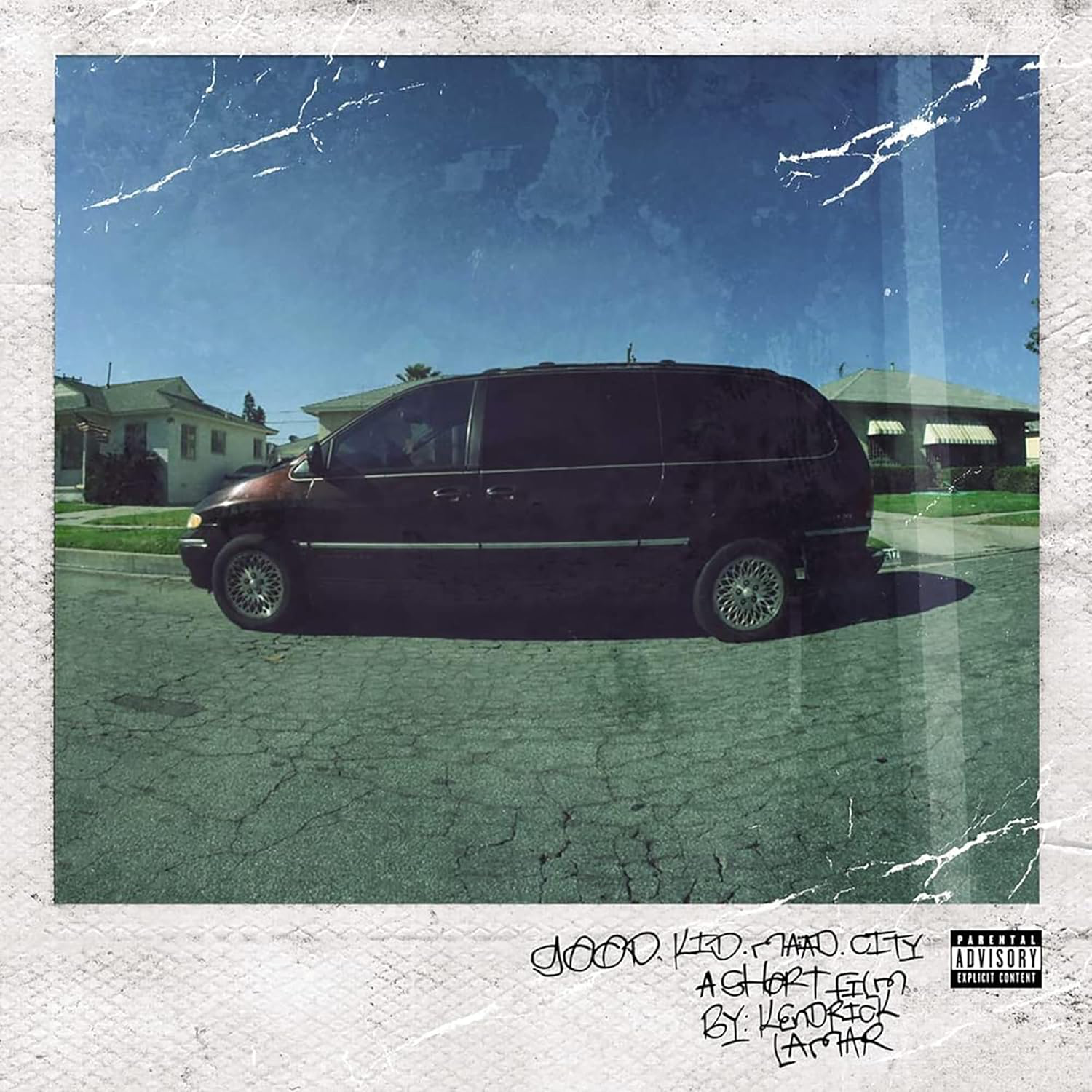

Over the course of the summer I tried very hard to get into Kedrick Lamar’s 2012 album good kid, m.A.A.d city (which I’m going to call GKMC).

GKMC is quite universally beloved, so I was surprised to find that I originally found it alienating. I guess I did not really understand what I was supposed to be looking for here. I knew it was a concept album, but none of the beats seemed catchy to me, nor did it seem to make a lot of sense—in fact, it struck me as rather cliched renderings of Kendrick’s lived experiences in Compton, which had been one of the primary focuses of hip-hop music for multiple generations at that point. My personal opinion was that pretty much everything that could be said about this topic had already been said by Nas’s Illmatic (although that takes place in Queens, not Compton). This was also exacerbated by the fact that the brand of hip-hop I was enjoying at the time was quite divorced from (the horrifically misnamed—I find it almost impossible to type this out without cringing) socially conscious rap, being mostly trap music. I mean, I was almost exclusively bumping summer staples in the vein of Kanye and Travis Scott, so it would make sense that GKMC didn’t really register.

A few days after watching Rachel Getting Married I decided to give good kid, m.A.A.d city another go, with the nagging suspicion that I would ‘get it’, this time. And after all that it seems to me that listening to GKMC as if it were a chronicle of the state of inner-city racial politics in America was foolhardy and reductive, although it is obviously that as well. After listening to it in full and listening to it again and again and again my only remaining thoughts were that this is an album for Kym.

I suppose there is a trivial sense in which this sounds foolish. These two people are nothing alike.

But insofar as there is a ‘point’ to GKMC it is one that can be unveiled by stripping the album back to its barest essence, kind of like how Radiohead’s OK Computer is only revealed once you get rid of the flashy guitar solos and synchronize with the album’s droning utterances about the sheer mental and physical exhaustions inherent to living in a modern society. And if you strip back GKMC you reveal a person who is profoundly scared and is engulfed in forces that they cannot understand and maybe even do not want to understand. What is common between Kym and Kendrick isn’t the kind of people they are but the kind of natures they share. Both of these people have a profound self-hatred for actions they committed but due to reasons that do not have anything to do with them.

The horror inherent in GKMC isn’t in the nature of the acts Kendrick describes himself committing or the lifestyles that he describes himself living but in the sheer inevitability of it. It’s in the fact that he was always going to turn out this way—that there does not exist a possible reality in which is not somehow assimilated into the gang culture he was raised in. And Kendrick obviously hates himself for it, but that begs the question—is it worth hating himself? How does he both own up and take the full brunt of responsibility for his own actions when his actions were merely expressions of a culture he did not choose to be born in and he had no say in doing? And it is this same culture which has both given him the ability to express himself on the record you are listening to while also instilling in him a blanket desire to ‘escape’ via the pursuit of money and power. And these are his primary preoccupations, sure, but is there a meaningful separation between the things that he as an individual wants and the desires that were inculcated in him by the nature of his growing up? Both these people struggle profoundly with God, and they do not know what it even means to seek forgiveness for an action that you were only partially responsible for. Does someone choose to be an addict?

These are all good questions with no answers. But I guess that the answer to the ultimate question posed by both of these people—is it possible to take responsibility for an act you were only partially responsible for, and had no meaningful say in preventing—is it possible to forgive yourself for the way that you are and continue to be, when you had no say in becoming that person—is that holding contradictory beliefs in your head isn’t really a fallacy to be ironed out but rather the default state in which human beings exist. Of course it is possible. And the ways that which human beings in this state express themselves goes beyond words. It is not explicable. And people are complex, and they can be cruel, but sometimes they really do mean well, and sometimes that is very hard to see.

same as it ever was

The writer of Rachel Getting Married is Jenny Lumet, daughter of Sydney Lumet, and as far as I can tell this was the only feature-length screenplay that she wrote.

I found Ms. Lumet’s contact information online, and wrote her a letter describing how much I enjoyed her film and whether she plans to write more; I am happy to eagerly await the cinema of anyone who has such a masterful and sensitive understanding of human beings and the constructs they invent around them. There is not a single moment during this film that I felt that something was off, or an event occured that did not fit in the mold of the others. These characters are real people, and this wedding really happened, if only on screen.

If Ms. Lumet responds, then I will update it here. I hope she is happy to hear that there are people out there who are getting joy from her work, and that her one feature film has deeply affected many people around the world, even thousands and thousands of miles away.