modernartposting

Last week I did two modern art1 things: first, I went to the Paris Internationale exhibition on recommendation of a friend of mine. Second, I visited a private artist’s residence (as part of a small group), where the artist in question explained her process and her ideology, and the meaning of some of her works. I came out of these experiences with two observations:

-

Never in my life do I feel more claustrophobic than while in the presence of contemporary artworks—as much as I like the idea of exhibitions, I have yet to go to one where I did not instantly feel the desire to flee.

-

I have less than zero interest in understanding the process of how art is created, regardless of the medium2. As far as I care, all art traces its lineage either to the big bang following which it simply fell out of the sky fully-formed, one day, or it was produced by creator during the literal worst moment of their life as a sudden epiphany, scrawled with charcoal onto the back of a love-letter they found lying under a bridge as they prepared to end their life.

I will now elaborate on these two things in tedious detail.

people should make art about football

I suspect that the strongest reason as to why I find myself alienated in exhibitions is because nearly everything I encounter at these events screams “this is not for you” to me similar to how I would imagine my ex-girlfriend used to feel while attending soccer games with me. She was always somewhat apprehensive at these events—this manifested in quite a number of ways, especially in the form of asking questions which I was somewhat baffled as to how to answer.

- What am I supposed to do? Well, I mean, watch the game, obviously.

- But am I supposed to cheer? Yeah, at the right moments.

- What are the right moments? You’ll see. We’ll all be cheering at those. Usually when someone scores a goal.

- So I wait till someone starts cheering? Sure.

- But then how do all of you simultaneously know you’re supposed to cheer at a particular moment? I’m not really certain, but, I mean, it depends on what our team is doing.

- Okay. Will your friends be annoyed if I cheer at the wrong thing? Definitely not. They want you there, you know. They’re going to love it if you’ll be there. They’ll be stoked to see you, they’ll try to make it as nice as possible.

- Hmm, but on some level they also don’t want me there. In the sense that it’ll be a bit annoying if you’re doing the wrong things, yeah, but trust me, they want you there.

- What do I wear? Well, I mean, whatever you want.

- Okay, I’ll wear my new top, then. Wait, isn’t that blue? Don’t wear that, that’s Man City’s color.

- So what do I wear? Red anything works.

- Your friends scream a lot. Yeah, but that’s kind of how these things work.

- I don’t get it. It’s thirty minutes in, and nothing’s happened. Wait, what? So much has happened. Didn’t you see Bruno miss ten minutes ago?

- This is so stupid. I don’t get it. What are you getting out of this? Yeah we’re down 4-0… honestly, no idea.

- Ooh, I like that guy, #7. He’s cute. Yeah, that’s, uh, Cristiano Ronaldo. He’s probably the greatest player in the world.

You know what I mean? This is basically my experience at exhibitions—there’s usually something there that I can synthesize, but a lot of it just goes entirely over my head, and the rest is there merely to alienate. Weird people dressed in off-putting ways, discussing things I can barely comprehend.

Of course, my first instinct is that there must be something I’m missing, which is true—the analogy I would draw here is an IT professional like my dad, for instance, visiting a cryptography conference. It’s not like there’s nothing he can gain from this, but by and large he does not possess the necessary skills required to gain the most out of this experience. In the sense of artists being in conversation with other artists, this is more or less true for me. My interest in art is merely passing and largely gained from frequenting museums and exhibitions. But unlike a technical field such as cryptography, for instance, it should not be the case that I obtain precisely nothing from looking at these works. Consider movies: you can show something like Mulholland Drive to a regular person and they would be able to piece something about it together; the experience is not entirely devoid of appeal, and even a more experimental work like, say, On the Silver Globe, atrocious as it is, can be of interest to non-cinephiles.

But a lot of these exhibits at the Paris Internationale seem to be pretty much nothing at all, and even in the cases where I can see what they’re doing they don’t seem to be accomplishing their function effectively3. Consider this piece by Eva Fàbregas:

which is accompanied by the following description:

Working with soft and malleable materials, Eva Fàbregas’ practice embraces tactile engagement, physical intimacy, sensorial relation and multiple forms of somatic experimentation with and through objects. Liberated from the constraints of biology, desire and affect are allowed to flow in all directions, blurring the distinction between organic and inorganic matter. In her practice, touch is a primary source of knowledge. Her work is about learning through one’s fingers and the sculptures are often reminiscent of body organs and voluptuous glands, but she also looks at prosthetics as well as non-human life-forms such as corals, polyps and the reproductive parts of plants. Fàbregas’ work belongs to the realm of the somatic, the experiential, the guttural and the unnamable. It aims to fully inhabit the world of the senses, invoking a pre-linguistic stage to imagine other possible bodies, other ways of feeling, caring and being in the world4.

The underlying idea here is not only clever, but really something very interesting in what it attempts to show: liberated from the constraints of biology, desire and affect are allowed to flow in all directions, blurring the distinction between organic and inorganic matter. I can see how the bulbous sculpture certainly looks like something that accomplishes this feat, but ultimately I am driven to boredom because it doesn’t seem to tell me anything at all about desire, affect, or the constraints of biology, which is what it promises. And this is a piece I don’t even dislike!

You know what else accomplishes this? JG Ballard’s Crash.

I can’t really articulate Ballard better than Mark Fisher does it, but the underlying ethos of artificiality in human sensuality induced by capitalism is quite unbelievable in Crash, which has innumerable things to say about every single one of the aforementioned things (and paints a pretty bleak portrait of them). But just because Crash is able to do this well doesn’t mean that an art piece can’t—the purpose of this was merely to show that the artwork isn’t attempting to do something impossible. Great—that’s is a start.

My next impulse is to say that Crash is, of course, a narrative form in the way that the sculpture isn’t, and it is undoubtedly true that narrative forms are better at doing the things that I want them to do. It is not hard to tell that I am a narrative form guy. I like books and movies. If that is to be considered, it’s not like I didn’t gain anything from the above sculpture—I liked looking at it, and even before reading the description it did feel like something weirdly biological, so I’m not being thrown off entirely. But then there’s things like this:

Like, I don’t know what this is or why it’s good or why it’s being shown to me.

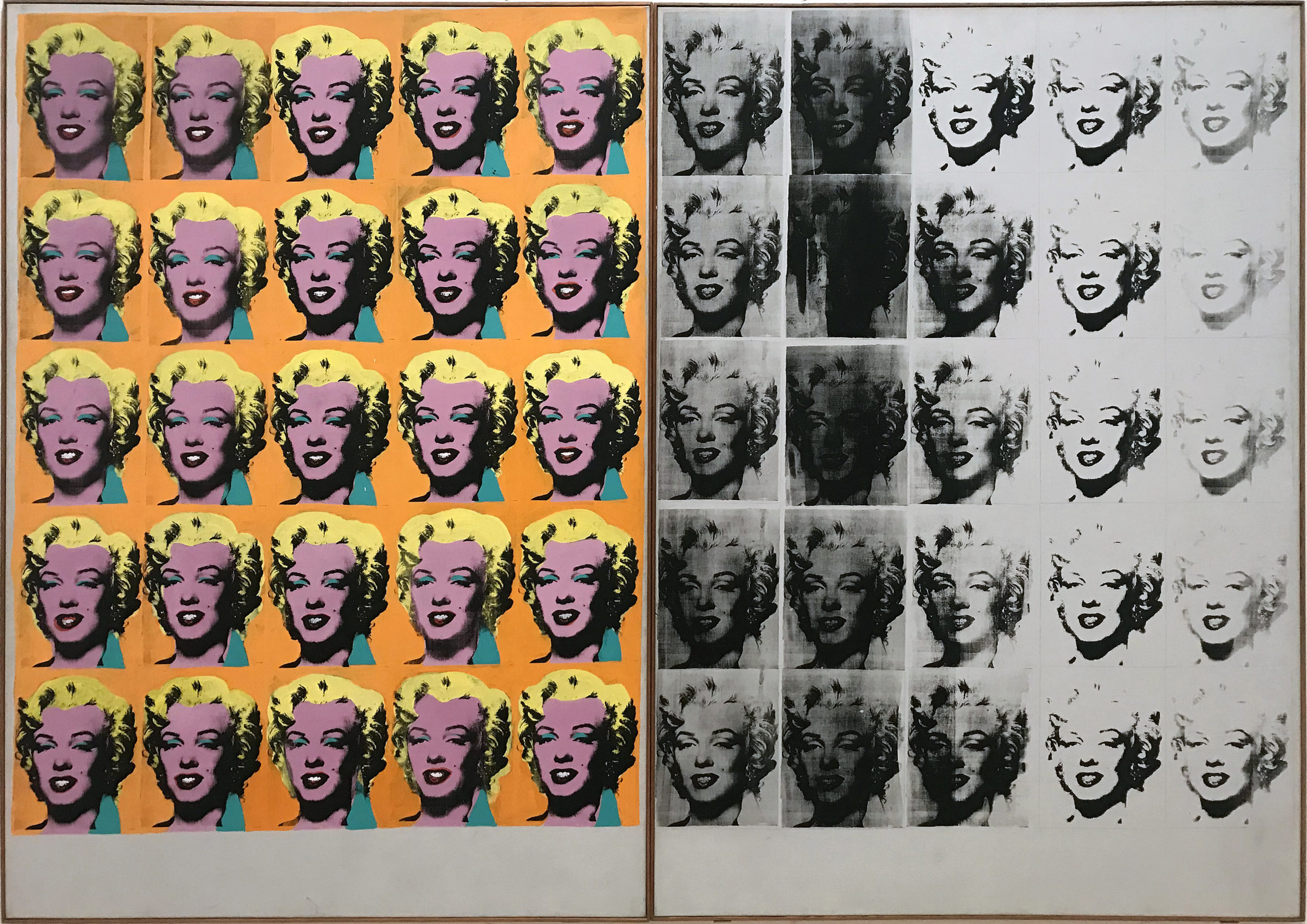

My limitations with experiencing non-narrative forms are a bit more general—it is also true that I find it a bit hard at art museums in general, though I think that might be a sensory perception issue; there’s too much I’m being bombarded with at any given moment, and by and large I enjoy looking at Monets and Van Goghs and Modiglianis. But it is also true that I mostly just like looking at them. Sometimes this takes a more cerebral slant, such as when I went to the Rothko chapel in Houston, way back in 2023, which consisted of a meditation room full of canvases painted pure black. Ideally this is the kind of thing I would think is stupid, but it turns out that I very much enjoy Rothko. First of all, he’s very good at putting me to sleep, which is an accomplishment on its own; I believe the purpose of his painting is to set a meditative mood, and I’m not being wry when I say that accomplishing this effectively is hard, and he does it very well. I am indeed moved by his musings on color as an object unto itself. The same is true for Andy Warhol, who is one of my favorite artists of all time:

The underlying sentiment here really is profound—Marilyn Monroe is very attractive, and I like looking at her, so I will look at her 50 times in different colors. That’s what pop art is, according to Warhol; “pop art is about liking things.” Isn’t that great? And, unlike Crash, it’s also just a static image, which shows that static images are good at expressing certain things. It’s just that barely any of the stuff I seem to see at the exhibition accomplishes this.

I guess my underlying takeaway from the exhibition is that artists don’t care about the things I care about. The good thing about the narrative form is that it can express anything that a static form can represent while also being entertaining, which is perhaps a pretty Warholian sentiment, on the whole. Cinema has Sátántangó, sure, but it also has Top Gun, and the point is Top Gun really is a very effective method of communicating certain themes. Maybe democratizing art isn’t that bad, after all—only all I see is either pretentious installations in upscale exhibitions or drivel from amateur artists online, and not really interesting forms of ‘democratic’ art that do what Top Gun is doing.

Here’s what I said to my friend upon completing the exhibition:

I have a question, how come all these artists are always talking about subverting things or challenging expectations or dealing with underrepresented classes and they all make the same transgressive sex outcast stuff?

I never see any art about football

To which she replied that I should take a look at the art of Matthew Barney, who famously makes art about football. Now I do know this guy, partly because he’s a famous avant-garde filmmaker and partly because Kanye called him Jesus at some point, and so I went in with high expectations. Here’s some of the football art:

Is it good? I don’t know, but I think this is probably the ultimate illustration of my previous sentiment about artists not caring about what I care about. What this piece is supposed to show is the masculine violence inherent in football. The problem is that I don’t care about the masculine violence inherent in football, I care about football, and after going through his work I have come to the conclusion that Matthew Barney cares about masculine violence more than he does about football. When I care about football I care about life-and-death greatness. I care about the game that DeLillo compared to nuclear war. I like the aesthetics of masculine violence in football, but when, like, Remember the Titans does it.

Ultimately, I do believe that there’s some manner in which the whole thing can be worked out effectively. Therefore I have decided to become an artist specializing in football. My first exhibit is a conceptual one: a complete collection of jerseys worn by all players during a single game framed and exhibited in a row as an illustration of what the shirt means and what damage they take during the game. Obviously, this is lowbrow, prole stuff—most of what I gain from football is best gained by simply watching the game, and this is not really a substitute for that—but that’s the point. This is commercial art for morons like me; the Top Gun of art, some would say, and I’m willing to bet that there are more guys out there who are going to be moved to tears upon witnessing this exhibit than the sum total of guys moved to tears at the Paris Internationale exhibition; though I suspect that if ‘number of guys moved to tears’ is the metric for artistic success, I don’t think it’s possible to do better than simply a television screen playing the same 30-second clip of Messi winning the world cup on loop.

the process is not the point

My other experience was more interesting, and perhaps more fruitful—I visited the house of a Mexican-born artist now living permanently in Paris, who works on abstract impressionism. This was part of a group of ten people. While I wasn’t the biggest fan of the art (although I did not dislike it) the experience itself was very interesting, and demonstrated innumerable things about what goes on in the mind of artists, while also demonstrating to me once and for all that I genuinely don’t care.

First off, I had a French Dispatch moment: similar to how Adrian Brody chastises the art collectors for disliking modern art by illustrating that the artist indeed possesses superior knowledge of technique—they are able to ‘draw a perfect sparrow’—the artist in question talked about how she used to make naturalistic sketches with charcoal and ink before arriving at her current works, and those sketches were indeed very very good renderings of people and the human body. Her new stuff is largely things like a single inkblot on a canvas. Now whether this actually does represent her themes is up to interpretation, but the art world certainly thinks it represents her themes, and I’ll leave it at that—since I have different priorities than them I can’t evaluate stuff the same way they do. However, this is a person who is not a hack by any means. She is very talented and very insightful, and knows a lot more about art and painting than I do.

Eventually I was shown a video meant to represent the ways in which women are ‘freed’, which consisted of videos of figs being broken open set to an audio of women gasping and moaning. I don’t think there’s anything I need to explain here—it’s quite straightforward, really, but the audience didn’t seem to think so. When she asked what our interpretation of this work was there was a guy who said that the fig has a strong historically feminine connotation, including how it is pollinated by the wasp, and so on, and while I do think this is not at all a bad observation I think it just serves to show how hollow the whole concept of symbolism is. The artist did not think of this; she was more attuned to the visual image of the fig—what it looks like—and based her artwork on that (I personally would agree that this is a better approach—certainly it’s the one I take). My broad problem with symbolism is perhaps my problem with art in general, which I guess just is symbolism in some sense—simply establishing the symbol doesn’t tell me anything about it. Consider, for example, a famous sense in which the fig is associated with womanhood, Plath’s fig tree analogy:

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out. I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

To me the fact that it is a fig tree is quite inconsequential; the analogy works just as well if it’s an apple tree, because it does not require the symbolism of the fig to do the heavy lifting. In fact, the fact that it’s a fig tree may very well be the least interesting part of the whole expression as a whole. But art seems to be profoundly concerned with the fact that it’s a fig tree in particular, and it is difficult for me to ascribe meaning to this connection in isolation, even if it is symbolically correct.

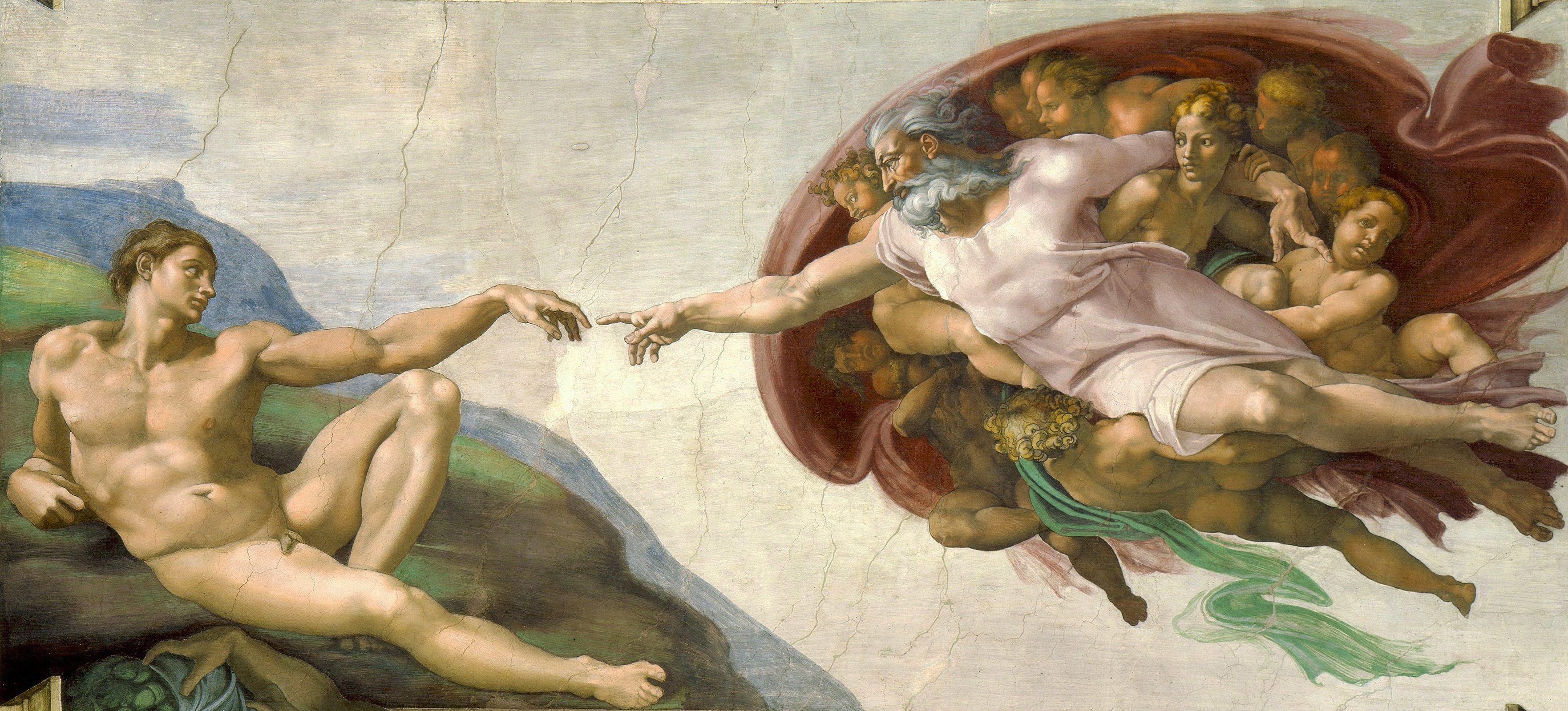

I have this problem even when symbol makes its way to metaphor or allegory. Fine, the apple is a biblical symbol, forming a tether to the Garden of Eden. Okay, and? If the work continues the allegory, I will similarly find it empty and devoid of richness because unless there is some radical step that brings to forth completely new interpretations of Genesis I could simply just read Genesis—which possesses all the thematic and psychological richness I need, because that’s not an ‘allusion,’ it’s just the work itself. If that’s the case, I probably just am the wrong person to admire art. I do like Biblical art, if that helps. If I walk into a cathedral I am profoundly moved, but I guess that simply is the ‘art for proles’ that I was talking about; something visceral that affects you at once, and makes you repent and believe in God for as long as you’re within the cathedral’s doors.

The next piece that the artist showed us was a collection of scratchings on a page which she had made while listening to music, and at this point I could barely follow anymore because if taken without the context of the music (as they were exhibited during the actual exhibition) I cannot make heads or tails of this. Which is why I state that the process gone into the art pretty much contributes nothing to my personal experience, unless it is a life-or-death matter—or rather, unless it’s a story that is as rich as the story expressed by the art itself. What I suspect I’m doing here is aestheticizing this process and synthesizing itself as an extension of the artwork, but if this story is somehow less interesting than the art I just don’t care about it.

‘I was doing this, and I had this idea’—I just can’t be bothered to care. Ultimately, it is never of much consequence to me what the author intended by a piece of work because the only way I can experience it is the way I do experience it. Sometimes it’s nice to know what they intended, but what is fascinating to me is only how I experience it myself. My take is the one I care about, and the take of other people who I know and care about and believe say interesting things, such as my friends or such as some reviewers I follow online. And I suspect this is why all these stories about production never have much allure to me as they do to other people. ‘Hey, Stanley Kubrick actually shot Eyes Wide Shut in London, not in New York City!’ And…? What am I supposed to do with this? Does it contribute to my experience of the film at all? Does it serve to illustrate how much of a genius Stanley Kubrick was? Evidently not, because I’m sure he could’ve achieved whatever he wanted to achieve simply by shooting in NYC, he was just lazy, and sure that’s funny, but that’s all it is.

But it seems like this is an integral part of the experience of contemporary art—the work itself should stand in isolation, and very often I am frustrated by works if I see the human flaws inherent in them. I don’t want to see the places where Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (one of my favorite movies of all time) falls apart. I don’t want to know how Disney made it. The film feels almost impossibly old, and I would prefer to think that this is an artifact that existed since the beginning of time and encodes something fundamental about the human condition in its pages; I would be a lot more interested in the story of its creation if it was a story of its discovery, for instance, wrought forth from Earth like Tutankhamen’s tomb, but that is untrue, and so inconsequential. I am not a theist, but it would be nice if it had its origin in God and not humankind.

So I had these experiences and they proved rather hollow, honestly, and while they did teach me about the things I like about art I must conclude that pretty much everything about the art world seems to prioritize things that I don’t care about at all, and this is not really for me, and that’s okay—there are enough artists out there without me joining their folds, and I am happy to keep reading my books and watching my movies; The Stranger, most recently, which I am planning to make the object of my next essay, and which partakes in very little symbolism and rather states its themes through the narrative, and therefore is something I believe I have quite an interesting grasp on indeed.

And yes, I know it is called contemporary art, not modern art, but the phrase is a nice catch-all and rolls off the tongue better—if Joyce has taught me anything, it’s that the most important attribute of a phrase is how it rolls off the tongue.

There are a few exceptions. Van Gogh is the obvious one. Although even the actual painting itself is usually extraordinary, knowing that he was hallucinating while making it strongly adds to the allure; you can say that in this case the art isn’t just the paintings, but also what went into making it. Somewhat like Fitzcarraldo, which is otherwise quite average as a movie. But both of these examples have a strong case as representatives of ‘worst moment of artist’s life’ paradigm I outline in the rest of the point.

Perhaps effectively is the wrong word; it is not the function of art to illustrate its point as well as possible, but in any case, certainly there should be some potency in how it does illustrate its point?

https://parisinternationale.com/artfairs/2025/exhibitors/bombon-projects?type=all#eva-fabregas-b-1988-in-barcelona.